|

|

|

J W North Working Notes

Working Notes

Working Notes

S P Milton

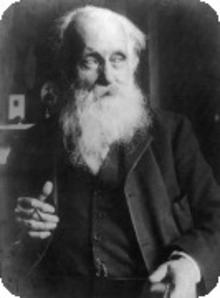

John William North, illustrator, watercolourist and painter in oils, was born in Walham Green, Fulham, London on New Year’s Day 1842. His father, Charles North (d.1890), was a draper - married to Fanny, both parents had been born in Fulham and there they kept a modest shop. Charles and Fanny had three other children, Charles two years older than John, Fanny, a couple of years younger and, Alfred born in 1847. The household also contained North's Grandfather, John North (b. Skipsley, Hertfordshire) and Eliza Knight who was described in the 1851 Census as a servant (b. Liss, Hampshire). According to North's biographer Herbert Alexander, his mother's maiden name was Knight, which may suggest that Eliza Knight was perhaps an Aunt. Alexander also states that North's maternal great - grandfather was a silversmith named Knight who worked in the City of London and became a master worker

around 1780. By 1851, the family was living at No 1 Frederick Place in Fulham. Not much is known of North's early life or schooling, although he later claimed that from the age of six he was:

"fond of reading and by the time I was eight I had read most of the Waverley Novels, Arabian Knights, Sandford and Merton, Evenings at Home, Robinson Crusoe and every other book I could get hold of."

From about 1850 North's parents began sending him on on a yearly holiday in the Country. The holidays lasted for about a month or six weeks in the summer. A sister of North's grandfather had married a farmer with the curious Saxon name Gathard and it was with them he stayed at their 100-acre farm near Kimpton in Hertfordshire not far from the Bedfordshire border. One incident is known - the young North was almost crushed to death in the crowds that lined the streets for the Duke of

Wellington's funeral. North's later childhood was marked by a series of traumatic upheavals. Maintaining a young family was placing a great strain on Charles and the drapery business and according to Herbert Alexander, the business failed in 1852 and Charles decided to start afresh in Worthing. Whether North went with the family is not clear and he may have stayed for a while with his Uncle Alfred a clothier in Fulham. Alexander states that North left school two years later at the age of 12 and was sent to work in his Father's shop (presumably at this time in Worthing?). However, he showed so little aptitude for the business that his parents gave him up in despair. Alexander quotes Ann North: "They didn't know what to make of him and let him go back to his sketching." It seems that, by 1854, a further failure in the drapery business occurred and Charles and Fanny's financial troubles became so serious that they decided to emigrate

to Ottawa taking with them their youngest son, Alfred. It seems that Charles (14), John (12) and Fanny (10) did not accompany their parents abroad. It is likely that the children divided their time with Uncle Alfred at 12 Princes Parade, Walham Green and with Great Uncle Gathard on his farm in Hertfordshire. Alexander maintains that between 1856 and 1866 he spent time with Uncles in Fulham, Brixton and Dartford. A sketch dating from 1854 was exhibited at the RWS Winter Exhibition in 1918 (No.173) - of Kimpton in Hertfordshire. It is known that North was reading 'The Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire' around 1856 which seems somewhat apposite given the disintegration of the family unit. North's artistic ability was obvious from an early age, although little is known of any formal training. It has been suggested that he spent periods at Marlborough House School of Art and the Times obituary refers to a period at

Lambeth. Herbert Alexander states that he received instructions from an artist named Hackman who kept a school near North's home in Fulham. A portrait of Alfred North and a still life both in oils said to have been mostly by this man but signed J.W.North. were noted by Alexander (now lost). It is known that North did receive some training and by the age of 10, he had assimilated enough to execute the watercolour painting - 'The Thames from Wandsworth.' The work of a red sailed barge and buildings beyond is now in the London Museum. North was obviously proud of the work and it was hung at the Royal Watercolour Society 1919 Winter Exhibition under the title 'Wandsworth in 1852' (No.223). He subsequently made a gift of the painting to Richard Lloyd of 103 Oakwood Court, London who presented it to the London Museum in 1927. Herbert Alexander noted other sketches of Harpenden, Wandsworth and Richmond Park dating from 1855 and he states

that North's first painting in oils from nature was completed in 1856 (and that it was at that time at Sheffield?). Alexander quotes Ann North: "He did not talk to us about his work, he went out sketching and we went too to keep away the children who wanted to look at what he was doing." Alexander states that there were three of his watercolours from this period in Sheffield (This reference to Sheffield is probably an indication that these works were in the possession of the family at the time Alexander wrote the notes - it has long been assumed that much of this archive was lost in Hong Kong during the 2nd World War). At about this stage in his development, HA recalled that North was helped by "an old painter" whose name he could not ascertain (presumably not Hackman) and for whom he did odd jobs in return. Ann North remembered this man but believed him to have been Josiah W Whymper (which sounds plausible, although Alexander

considered it unlikely, as he was not at that time an old man) HA also noted a sketch of Chelsea and "a large number of watercolour skies probably done at Walham Green." This is noteworthy only because later critics have claimed that North had trouble with his handling of skies. Several works dating from 1857 were subsequently exhibited: 'From the Downs behind Ventnor' (RWS Winter Exhibition in 1911), A pencil drawing 'Broadwater Rectory Farm, Worthing, Sussex' - "Drawn on the spot, December, 1857" (RWS Winter Exhibition, 1916) 'View of Franks Sutton at Hone, Kent 1857' (RWS Winter Exhibition 1918). Alexander recalls that North told him that from the age of sixteen he had earned his own living, so it must have been in 1858 that he started work for Josiah Whymper the successful London wood engraver. In 'The Life and Letters of Fred Walker' by H S Marks there is a description of Whymper's working arrangements. North, if

engaged upon similar terms as Walker (and it is likely), would have worked for Whymper two or three days each week at a weekly wage producing drawings for the wood. The apprentice would have the remaining days of the week free for study or other work. Among North's fellow employees at Whymper's were Fred Walker and later George John Pinwell. North established a friendship with his employer's son Edward Whymper's son Edward the famous Alpinist - first man to climb the Matterhorn. The two began making walking trips together and it is possible that they visited Switzerland together - Whymper was certainly there in 1860 and 1861. A North drawing engraved for Jean Ingelow's Poems shows a view of the Mischabel chain above Saas Fee in Switzerland. A figure in the forground of this drawing is presumed to be Edward Whymper - an illustration by Whymper's of himself from Scrambles amongst the Alps looks pretty much like

the same person. Whymper and North could only have been together in Saas Fee in June 1862 or Sept 1861 although Jean Ingelow's Poems was not published until 1867 which needs some explaining. Much of North's early black and white work for Josiah Whymper was destined for publications by the S.P.C.K. and the Religious Tract Society. Some illustrations were also published by Swain (not yet traced). His work (and probably his conscientious approach to commissions) was obviously well regarded in the trade and from 1862 to 1867, North worked for the most prominent illustrators of the day including the Dalziel Brothers. There he gained a reputation for his sensitive interpretation of landscape subjects. He made designs for periodicals including Alexander Strahan's Good Words (in 1863 and 1866), Once a Week (between 1864 and 1867) and The Sunday Magazine (between 1865 and 1867). In addition, he contributed to A Round of

Days (1866), Wayside Posies (1867) and Jean Ingelow’s Poems (1867). Following North's death Gilbert Dalziel wrote a short article recalling North's time with the Firm: "Much of (North's illustrative work) was drawn direct on the woodblock. Happily, when photography-on-the-wood became more perfect; he made his drawings on card or paper, and these were photographed on to the wood block and then engraved. Several of these "originals" are still in existence to testify to the refinement of North's work in black and white. In this connection, it is incorrect to speak of his "pen-work"; for never in his life did he use a pen. It was mainly all brush work; but if need be, he would at times use a hard pencil for very fine lines and minute detail. His finest work is unquestionably to be found in many of the guinea Gift Books produced by the brothers Dalziel during the sixties. Take for instance "Wayside Posies" published by

Routledge in 1867 and on page 30 look at North's drawing to a poem entitled "Reaping". Where could anything grander be found in black and white? Colour, execution, design with the very breath of Nature pervading the whole thing, makes it a wonderful achievement. Again, on page 62 of the same work, his illustration to the poem, "A Vagrant's Song" is a masterpiece of refined delicacy. The general effect of sunlight in the distance is quite remarkable. Dozens of similar examples could be quoted. His work in "A Round of Days" published by Routledge in 1866 is equally beautiful; while in "Jean Ingelow's Poems" published by Longman in 1867, North seems to have surpassed himself!" In 1860, the eighteen year-old North and twenty-one year-old Edward Whymper went on a walking tour of West Somerset. Alexander recalls that he stayed on the first trip at Watchet and that Pinwell may also have been there. Here North

first discovered and sketched Halsway Manor a crumbling C15 Manor House near Crowcombe under the western flank of the Quantock Hills. At that time the Manor was held by James Crang and farmed by his tenant William Thorne. It is certain that Pinwell was in Somerset with North in 1863 because Alexander records a sketch of Pinwell by North lying in long grass at Axmouth. Several of Pinwell's illustrations feature Halsway and its environs. North was particularly drawn to Halsway Manor and soon made arrangements with Mrs Thorne, the tenant's wife, to rent a room in the splendidly dilapidated house. The Manor was originally built as a hunting lodge by Cardinal Beaufort, half- brother of Henry IV but had passed through many families and undergone many changes before ending up in the possession of James Crang. North stayed at Halsway on and off for over six years until January 1869 when the Crang family again took possession

and began the renovations that preceded its sale to Charles Rowcliffe, a solicitor, who lived at Cagley Court in nearby Sampford Brett. Mr and Mrs Thorne moved to the nearby village of Woolston and North decided to go along with them. The Halsway Manor that North discovered has undergone major renovation over the years and is today a Folk Music and Dance Centre. The years between 1860 and 1867were successful for North, his illustrative work was in demand and regular commissions for 'Good Words' and 'The Sunday Magazine' provided a reasonable degree of pecuniary comfort. He divided his time between London and Somerset where he was beginning to develop his peculiar watercolour technique. According to R M Billngham, North completed a finished watercolour of Halsway Manor in 1865. This work, which is inscribed "North.65", is (was?) in a private collection in London. The drawing of the same subject was acquired by the Victoria

and Albert Museum in 1909, and according to the catalogue entry, the figures were added by Pinwell. I have been told (but have yet to check), that a completed picture of a similar scene was sold at Christie's in 1985 for £30,240. In the same year, North completed a large watercolour landscape with poppies that was subsequently sold at Manchester in 1925 for a mere £18 - I can find no record of this painting having been exhibited. It was around 1866 that North's parents returned from Canada having failed to secure a living. According to Alexander, the responsibility for the whole family then fell on John. He took a cottage for his parents in Potter Street, Essex and he placed his younger brother Alfred at Rawdon Baptist College in Yorkshire to train for the ministry. In the same year, His elder brother, Charles, died of tuberculosis in Brixton, the burden of care again assumed by John. 1867 saw the publication by Routledge

of "Wayside Posies" and by Longman of "Jean Ingelow's Poems." This represents the pinnacle of North's achievement in black and white and, buoyed by the success, he determined to abandon illustration for painting in watercolours. The end of the year brought a setback for North as he failed in the elections for membership of the Old Watercolour Society (Royal Watercolour Society). Fred Walker wrote a consoling letter to his friend in Somerset conveying the regrets of Burton and John Gilbert who had both supported his election. Walker indicated that the reason North "so narrowly missed going in was a certain opinion some of the members expressed, that there was a want of finish in parts" of his work. This must have been a blow for North for he was painstaking in his methods and (as he pointed in later correspondence) he laboured assiduously over every work. In the same letter, Walker extended an invitation to North to come and stay

and it is likely that this invitation was accepted. Walker was on the RWS hanging committee and it is hard to imagine North turning down the chance to further discuss the reasons for his failure in the election. He may have met William Graham on this visit. Graham was already acquainted with Walker, and a correspondence between North and Graham began in this year. Graham (later MP) would become one of North's main patrons. In April 1868 North returned the kindness and invited Fred Walker down to Halsway. Fred Walker was on the up. He had already secured an impressive reputation for his early watercolours - the pre- Raphaelite influenced ‘Strange Faces’ exhibited at the RWS in 1862 and the more assured ‘Philip in Church' which appeared in the following year. At the age of 23, he had already been denounced by Ruskin for betraying his genius, for over experimentation and for refusing to learn from past masters. He had been awarded a medal at

the Paris Exhibition and had won the admiration of William Hunt. His 1864 watercolour ‘Spring’ had been a smash hit and brought rapturous acclaim from all quarters. With the 1863 oil 'The Lost Path’ he had wowed the Royal Academy but created something of a critical storm with ‘Wayfarers’ in 1866 and ‘The Bathers’ which appeared the following year. He was a visitor to Millais, Birket Foster and Tennyson; he socialised with Landseer and Lewis. Walker was 'in' - he was a celebrity - he was part of the artistic establishment. In the middle of this critical and social melee, Walker decided to visit "old North" in his Somerset retreat. During the years 1866 - 1884 North divided his time between Woolston Moor (and other addresses nearby), a house built for him in Algeria and his London studio in Charlotte Street (now the site of the Telecom Tower). He visited Scotland on at least one occasion in the early 1870s, probably as a guest of

his patron William Graham MP, and painted views on the River Tay at Stobhall. North’s watercolours of the 1860s show the marked influence of his previous work as an illustrator. Generally, the pictures have a strong two-dimensional composition. Often the close-cropped primary focus covers the canvas completely with little use of distance or traditional recessional perspective, skyline or horizon. As if newly relieved of the constraint of black and white, North's 'Grosvenor Gallery Phase' is marked by the use of intense and occasionally unconventional colour. At this time, his careful observation of detail borders on painstaking, evidence of his early Pre- Raphaelite influences. In time he moved away from this approach, finding a less literal, more suggestive (but no less time-consuming) technique. Adhering to the Pre-Raphaelite, Ruskin inspired manifesto, North always worked direct from nature in the open air -

right until his death. According to Walker, writing in December 1868, ‘each inch wrought with gem-like care.’ (J.G. Marks, Life and Letters of Frederick Walker, A.R.A., London, 1896, p.165). There is an entry in the Herbert Alexander notebook that confirms that North was introduced to the writer Richard Jefferies by Joseph Comyns Carr in 1883, the same year that Jefferies made his visit to Somerset to research material for ‘Red Deer’ and the posthumous ‘Summer in Somerset.’ Alexander’s notes were based on recollections of conversations with North and there is no reason to doubt his assertion on this point. Comyns Carr was already well acquainted with North from their association with the Grosvenor Gallery. He had graduated in law from London University in 1869 and later became art critic for the Pall Mall Gazette under the editorship of Frederick Greenwood. Jefferies claimed to have been associated with the PMG

from the late 1860s, although it seems that a more formal relationship with this publication began around the middle of the next decade. North was a reader of the PMG (and occasional contributor) and this may have brought him into contact with Jefferies’s writing. Since his early days on his Uncle’s farm North had understood the reality of the countryside and his painting clearly reflects this. So the term Idyllist may seem puzzling. It has to be remembered that his early work in black and white was usually to illustrate a literary narrative. Once free from the industry of illustration, North never did portray the sentimental chocolate box scenes of country life in the manner of Birkett Foster or Allingham and the narrative style was often completely absent from his work – it was always present in Walker and Pinwell. In many of his best works, figures although present are generally subordinate or incidental to the scene –

the focus is nature. The Idyll that North seeks to reveal seems to be about inner revelation or rapture - human spirit and emotion defined within a natural context. Like Jefferies, there is an element of mysticism in North's work. In Jefferies's nature writing, time seems irrelevant and deeper truths are hinted at but not completely revealed – an idyllic state of oneness with nature. North and Jefferies had things in common. Neither had a university education - both were largely self- taught - and both acquired a deep love of literature from an early age. They had inquiring minds and shared a keen sense of social justice. Both were unconstrained by convention and Victorian morality. Often radical in outlook, both understood the reality of country life and sympathised with those who lived it. Above all, they seem to share a similar reaction to nature. North was a fervent campaigner for the agricultural labouring class,

championing their cause in the national and local press. He opposed the enclosure of common lands on the Quantocks under the Game Laws and he campaigned for decent rural sanitation and for social housing. He was Liberal in both conviction and politics but his sympathy for the plight of the agricultural labourer came from direct first hand knowledge and observation and not from a metropolitan political viewpoint. Alexander suggests that for North fighting the battles of the agricultural labourer was a ‘labour of love, and he called it his recreation.’ This sympathy is greatly evident in his pronouncement before the start of WW1: “And if Germany were to conquer England, I don’t see that it would matter, for if, as you say, she is so splendidly organised she might improve the state of England’s agricultural labourers, which could not be worse than it is now.” A little of Jefferies’s spirit is clearly evident in this remark. North, later change his

view on the war. Comyns-Carr’s editor, Frederick Greenwood was an early admirer of Jefferies and later proudly recalled that he had been among the first to publish his work. He wrote: “One or two of those beautiful books of Jefferies first came out of the Pall Mall, all to an exasperatingly small amount of attention, a not inconsiderable amount in itself, but so much less than their manifest worth and charm deserved as to be painfully disappointing to Jefferies’s editor.’ In a letter reproduced in Robertson Scott’s ‘Story of the PMG’ Jefferies confirms that this association with Greenwood was mutually appreciative; he very much valued his advice – indeed Jefferies offered Greenwood a share in the proceeds of 'The Gamekeeper at Home' in acknowledgement of his valuable editorial assistance. Greenwood was an influential figure and his support did much to advance Jefferies’s career and bring his work to a wider and more aesthetically

appreciative audience – for example it was Greenwood who in 1878 urged the reluctant publisher George Bentley – he had previously declined Jefferies’s work - to give serious consideration to the novel 'Green Ferne Farm'. North was on close terms with Comyns Carr and they shared a mutual circle of friends and associates through their connections with the Grosvenor Gallery, the New Gallery, the Arts Club and in Carr’s case the Rabelais Club. North had been a member of the Arts Club since 1874 and had been exhibiting at the Grosvenor Gallery since at least 1882 but more probably since it's opening in 1876. Sir Coutts Lindsay had appointed Comyns Carr press representative for the Grosvenor Gallery and later co- assistant along with Charles Hallé. The Grosvenor became a focus for those artists opposed to the anachronistic values of the Royal Academy - an institution forcibly denounced by Comyns Carr. However, in 1888 he and Hallé left the

Grosvenor Gallery to set up the rival New Gallery on Regent Street, taking with them Lindsay's greatest asset, Burne-Jones. North switched allegiance too and was appointed at once onto the ‘Consulting Committee’. Through his friendship with Carr and by virtue of his associations with these artistic institutions North became part of an aesthetic circle that included George Meredith, Barbara Bodichon, Thomas Hardy, Oliver Wendell Holmes, Victor Hugo, Henry Irving, Henry James, R.L. Stevenson, Burne Jones, Whistler, Charles Hallé and Walter Besant. As a friend and critic Comyns Carr was well acquainted with North’s paintings of the West Somerset landscape, and he was no doubt intrigued with the fascination this remote part of England held for the Idyllist group of painters. Indeed Carr had written an early monograph on Frederick Walker. It is unclear if Carr ever visited North in Somerset, but we can assume that Carr knew the area through his

familiarity with the work of North and Walker. This interest was significant for it seems that it was Carr who suggested that Jefferies make a trip to Somerset to write a topographical article for the newly launched English Illustrated Magazine of which he was editor. North was persuaded to illustrate the article. 'Persuade' is probably correct because this project could not have been of commercial interest to North who at this time was approaching the zenith of his fame and wealth (from 1871 his exhibition paintings had been selling for over £200). So this may have started out as a favour for Carr, unless of course North was already an admirer of Jefferies. It has been suggested by a Jefferies scholar, that Carr may have promoted and financed the trip himself and this could explain why he needed to arrange an introduction. The introduction was arranged and in June of 1883 Jefferies was in Somerset. Jefferies’s visit to Somerset was a

brief one, lasting maybe two weeks at most. However, it was a successful trip that produced material for ‘Red Deer,’ ‘Summer in Somerset’ and other articles. During his stay he was able to explore a large area stretching from West Bagborough on the eastern flank of the Quantock Hills - about 5 miles west of Taunton - across the Brendon Hills, right along the Severn coast to Porlock Weir and beyond to Oareford a distance of some 30 miles. Memorably, Jefferies walks the banks of the River Barle following its course upstream from Dulverton to Tarr Steps and beyond. Dulverton lies on the southern flank of Exmoor some 10 miles inland from Porlock Weir. It is hard to trace Jefferies’s steps using only the published texts as a guide and his narrative occasionally hops from place to place ignoring the inconvenience of distance or geography. For example he “drifts” from Dulverton back to The Quantocks – a hard march of at least 16

miles. It is clear that Jefferies started his exploration of West Somerset from the Quantock Hills. The late Berta Lawrence recalls a conversation with North’s daughter Bet North that supports the idea that Jefferies stayed with North while in Somerset. The Alexander notes also contain a reference to a “visit” in this year – although this may simply mean the visit to Somerset. It is a comfortable deduction, Stogumber and Williton stations are both less than a couple of miles from Bicknoller where North had lodgings – so it would have been a convenient arrangement. Jefferies refers to Bicknoller in ‘Summer in Somerset’ describing the ancient cross and he clearly explored the area for a day or two making walks onto the Quantock ridge and into Holford Combe – a spot well know to North. His rambles in this area suggest very strongly that he had a local guide – someone to point out the local antiquities and places of interest. For

example, Jefferies refers to Walker’s painting grounds referring specifically to one of Walker’s works – ‘The Plough,’ and who would of known these places other than North? The background of ‘The Plough’ - a crumbling honey coloured quarry - can be found not more than a few hundred yards from Woolston where North and Walker had been lodging with Mr and Mrs Thorne. Curdon Mill, with its undershot wheel, can be found on the road to from Woolston to Stogumber and it also features in Jefferies’s narrative. The buildings are preserved still. From Bicknoller, Jefferies seems to have travelled on through Williton, Bilbrook (where Dragon Cross is mentioned) and Dunster to Minehead. From Minehead he explored the area around Selworthy before making for Porlock Weir where it appears he took or considered taking accommodation at the Anchor Hotel. He certainly explored the area around Porlock including the beautiful woodlands of

the Holnicot estate and beyond to Cloutsham and Dunkery Beacon. From Porlock it is a relatively short journey to Exford where much of the material for Red Deer was collected with the help of his guide – Fred Heal. The account of the Barle in 'Summer in Somerset' suggests that from Dulverton Jefferies then travelled back to the Quantock Hills and to West Bagborough, so it is quite possible that his trip to Somerset began and ended in the company of North. Jefferies’s friendship with North lasted for the remaining 4 years of his life. North made at least two visits to Jefferies and his family. In a note made the day after Jefferies’s death North refers somewhat obliquely to a meeting four years earlier at Eltham (although Jefferies had been living in Brighton in 1883). There is only one known surviving letter from North to Jefferies dating from March 1886. In the letter North plans a further trip to Crowborough (confirming a second

visit had been made and suggesting that a third was imminent) and discusses details of family illnesses and bereavements - here he also refers to Jefferies’s previous letter, which must have touched on his deteriorating health. The letter concludes with some observations on wildlife. The friendly and intimate tone of the letter is obvious. Alexander notes correspondence from Jefferies to North in 1887 but sadly these letters are no longer extant. Jefferies obviously valued the friendship and sent North inscribed editions of his later works, which are still in existence. On 14th August 1887 at 2.30 pm in the afternoon North knocked on the door of ‘Sea View’ Goring. No doubt he had been informed of Jefferies’s final decline and was hurrying to be at his friend’s bedside. Perhaps the door was opened by Jefferies’s servant girl, Jennie Moss; the tragic scene that confronted North moved him deeply, for Jefferies had died some 12 hours before

his arrival at 2.30am in the morning. North’s account of the scene (written in the style of a letter to his wife - note the reference to ‘dear’) speaks for itself: "Monday, 15th August 1887 I went yesterday expecting to once more speak with him. I found him lying dead, twelve hours dead. I saw him with Mrs Jefferies and their little Phyllis. A pitiful sight to see them kiss the poor cold face! God help them! … The poor dear wife seemed to feel the change which death had brought upon the dear loved face almost more than all the rest. “Oh, how he is changed! A few hours back he was himself. How can I bear it? But they tell me he will again look better.” When I tried to dissuade her from looking upon him she said: I MUST – I MUST; until he taken away I must see him and kiss him each time. My Phyllis, you will never see your dear papa without kissing him?” “No, no,” said the little one, and she had no

fear in the presence of death. You know, dear, how hard life was with them. All through his last days his wife was with him day and night. She had no hired nurse; their only servant (a young country girl who behaved nobly throughout) was her only help… His long, long illness of six years (you remember how near death he looked when you saw him first at Eltham four years back) – this long, wearisome time had almost persuaded many who knew him not intimately that this illness was partly imaginary. He has proved it otherwise. A soldier who in health and high spirits, and excitement, rides to what appears certain death is called a hero; glory and honours are heaped upon him; but what is that compared with years of fighting without cessation, and absolute certainty of defeat always present to the mind. I asked Mrs Jefferies if he had made a will. “No surely it would have been useless; we have nothing. A woman singly, strong as I am, could rough it;

but if something could be done for the children I shall be thankful.” I had to call at my framemakers’s to put off an appointment. I told him roughly what had happened to me yesterday. He had never heard of Jefferies, knew nothing of his work; but he said, “I shall be glad if anything can be done if you will put me down for two guineas.” You, being both country born and bred, and with a heart inside your body, have always, sometimes to my surprise, recognised and admired poor Jefferies’s writing.” North then adds further notes, clearly written some time after the event: “Shall I tell you what I think and know, that in all our literature until now he has never had a rival, and it is most unlikely that he will ever be equalled. In a hundred years he will be more truly appreciated. The number of men who combine the love and knowledge of his subjects with the love and knowledge of literary work is more limited perhaps in this age than in any

previous one. Few people of intelligence and refinement of heart and mind live completely enough in the comparative solitude of the country, and much, perhaps most of his work, will always be unintelligible to those who cannot exist in a country house except it is full of frequently changing guests. I have been trying by a different art for thirty years – equal to almost the whole of his life on earth – to convey the idea to others of some such subjects, and I feel with shame that in the work of half a year I do not get so near the heart and truth of nature as he in one paragraph. With strict charge that it should not leave my hands Mrs Jefferies lent me the proof of an article which appeared in Longman’s Magazine in spring, 1888. It was the very last copy he wrote with his own hand. Since that time his wife wrote from his dictation. I will try to get it for you, but in the meantime read this quotation, which touched me

greatly yesterday:- “I wonder to myself how they can all get on without me – how they manage, birds and flower, without ME to keep the calendar for them. For I noted it so carefully and lovingly, day by day.” And this:- “They go on without me, orchis flower and cowslip. I cannot number them all. I hear, as it were, the patter of their feet – flower and buds, and beautiful clouds that go over, with sweet rush of rain and burst of sun glory among the leafy trees. They go on, and I am no more than the least of the empty shells that strewed the sward of the hill.” One thing I saw in his last notebooks: “Three great giants are against me- Disease, Despair, and Poverty.” Almost his last intelligible words were: “Yes, yes that is so. Help, Lord for Jesus’ sake. Darling, good-bye. God bless you and the children, and save you all from such great pain.” “In the gentlest, sweet, soft, sunny rain he was born along the path to his

grave in the grass; and when the last part of the service for the dead was read, well and solemnly, and we turned away leaving him for ever on earth, the large tears of Heaven fell thick and fast, and over and over again came to me the saying, ‘H apply are the dead that the rain rains on.’ The modest home-made wreath of wild-wood clematis and myrtle my wife had sent, pleased me by happy symbolism – for as the myrtle is, so will his memory be ‘forever green’ ” North concludes his eulogy with verse. Hopefully one of you may recognise it, so far I have failed to attribute it and have a suspicion that perhaps North himself may have penned this most beautifully appropriate homily: “Mourn, little Harebells o’er the Lea;

Ye stately Foxgloves fair to see;

Ye Woodbines hanging bonnilee;

In scented bowers;

Ye roses on your thorny tree

The First of flowers. Mourn, Spring, thou darling of the year!

Ilk

Cowslip cup shall kep a tear;

Thou simmer while each corny spear

Shoots up its head,

Thy gay, green, flowery tresses shear

For him that’s dead!” Having witnessed the most deeply affecting scene of the day before, North wrote immediately to the Pall Mall Gazette calling for donations to help the widow and the family. His appeal was published on Tuesday 16th August 1887. An insight into the efforts made by North to discharge this last duty to his departed friend is provided by some surviving correspondence between North and Charles Churchill Osborne of De Vaux Place, Salisbury - editor of that City’s local newspaper the Winchester and Salisbury Journal. In the letters we find that North was unaware that another fund was already in existence. This is probably a reference to the fund established by C P Scott of the Manchester Guardian that had pre-dated his own appeal in the PMG by some

months. If so, then North must have been unaware of Scott’s friendship with and support for Jefferies. By the time of North’s appeal, Scott’s fund stood at over £200 (At this time Jefferies gave his annual earnings at only £50). It was Scott who had assisted Jefferies to submit an application to the Royal Literary Fund for relief of his immediate pecuniary crisis. Osborne himself had launched an appeal in the ‘Salisbury and Winchester Journal’ and had obviously written to North making him aware of it. Various other funds are referred to in North’s final published accounts – the Langworthy Fund being the most notable. In his letters to Osborne, North tells how he labours until 2.30am in the morning personally answering every letter in connection with the fund. Much debate surrounded the choice of Trustees for the fund and various names are mentioned. Most seemed unwilling to take on this onerous duty and North

himself was not inclined to put himself forward. Some of those approached by Osbourne (and indeed Osborne himself) seem to have been slightly suspicious of any undertaking associated with the radical campaigning and Liberal supporting PMG. It seems too, as if Osborne first suggested to North the idea of a memorial bust in Salisbury Cathedral and after consulting Jefferies’s widow North replies enthusiastically: “ I can tell you that yesterday Mrs Jefferies seemed more touched and pleased by the idea of recognition in this way in her and his native county than in any other means I heard.” It was Osborne who suggested an application for a civil list pension on behalf of Mrs Jefferies and North warmly encouraged the idea inviting him to “speedily draw up an independent petition to the Treasury.” North, never one to rely totally on others, took a personal interest in the prosecution of this application, calling on Louis

Jessop M.P considering that "the best way to influence the government is through the members of Parliament." North had no great faith in formal petitions. On 27th August, 1887 a letter from North appeared in the ‘Standard’ referring to the RJF. This may have been an effort to broaden support and free himself “from the taint” of the PMG. In a letter the following Monday, 29th of August, North provides some biographical details for Osbourne who seems to have been unaware of Jefferies’s place of birth or personal circumstances. He adds a description of Jefferies’s long illness - it is a detailed account and one that suggests that their friendship must have been of a frank and intimate nature. Indeed in the same letter North adds that he was “perhaps the nearest personal friend of Jefferies.” Among the other interesting fragments in this letter is a reference to an approach made by Mr Arthur Kinglake of Taunton to Mrs Jefferies seeking to

offer a position to Jennie Moss. Kinglake, who had also launched an appeal to assist Jesse and the Children in the Morning Post, was later instrumental in the commissioning of the marble memorial bust by Margaret Thomas for Salisbury Cathedral (a copy of which stands in the Salisbury Council offices). By September, North had secured the support of W C Alexander, Banker, of 24 Lombard Street, London to act as treasurer of the RJF - Alexander himself had made a generous donation to the fund of £100. Still no Trustees had been found although plans were now in place for the disposal of the funds. The interest on the accumulated fund would be applied to Jesse, until the children came of age when the capital would be applied for their benefit. North had already arranged for £140 to be paid to Jesse to help with her immediate necessities. On Saturday 17th September 1887 at North's request Jesse, Harold and Phyllis arrived at Beggearnhuish House

in West Somerset. She and the family would stay with North for several months (she was still there in January 1888) until her immediate financial situation was secure. This must have been of great comfort to the grieving widow. North busied himself making arrangements for the 12-year-old Harold's education. North described the young student as 'a handsome lad, very tall for his age with exceedingly fair hair and with plenty of vivacity and fairly well up in the three R's.' On Monday morning on 3rd October Harold walked through the gates at West Somerset County School in Wellington. Later, Richard Harold Jefferies recalled his days at Beggearn Huish House, "especially playing in the splendid orchard...with its many varieties of apples and other fruit. The orchard was on a considerable eminence...at the rim of a railway cutting, where I could indulge one of my favourite pastimes, watching trains." These would have been the

engines and mineral trucks passing along the nearby West Somerset Mineral Line carrying iron ore from the mines on the Brendon Hills to the nearby port at Watchet. On Sunday 25th September Jesse received the very welcome confirmation that the Treasury had made an award of £100 per annum from the Civil List - and so within a six weeks of Jefferies's death his family's financial worries were at an end. There is in this a sort of tragic irony. Jefferies's last years had been spent eking out a meagre living and worrying what would happen to the family after his death. With financial matters resolved, Jesse and North turned their thoughts to Jefferies's papers. Several publishers had agreed to republish Jefferies's articles in book form and Walter Besant had promised to write a memoir and preface to the volume. He visited Jesse and North in Somerset during October to look through the papers and it seems that the idea of a memoir was abandoned

in favour of a full-blown biography. This as we know was - The Eulogy. With Trustees now appointed - Besant, Alfred Buckley and C Jefferies Longman having agreed - North finally published a full statement of the consolidated accounts for the RJF on 1st January 1889. This fascinating account contains the names of all the subscribers and can be viewed on my website. The various appeals had raised a total of £1,514 pounds which would provide an annuity of around £150 for Jesse and the family. This, augmented by the other pensions and earnings from the posthumous publications, secured for the family a reasonable income. At the Royal Watercolour Society in 1888 North presented his own personal eulogy to Jefferies under the title, 'Sir Bevis and the Wood Woman.' This large watercolour depicts a sunlit woodland scene in autumn, a woman in the foreground with a billhook in hand. In the distance we see Sir Bevis, a

blond haired boy, fighting off a swarm of bees. This is North at the zenith of his powers. The last golden leaves hang from the trees and a glow of ethereal sunlight suffuses the scene. On the left is a stream and on the horizon we can see the outline of the Brendon Hills. There is an obvious symbolism. The rustic billhook, the woodman’s equivalent to the scythe, can be seen as a symbol of death, and although it glints in the autumn sun it seems somehow insignificant. The power that death holds over mortal man seems is transfigured by nature’s power of eternal regeneration. This may be North's take on Jefferies's message: “The hours when the mind is absorbed by beauty are the only hours when we really live, so that the longer we can stay among these things so much more is snatched from inevitable Time.” Ironically, the painting has humorous touches in the figure of Sir Bevis -

his sharp yelps breaking the reflective mood. North must have started this painting immediately on his return from Jefferies’s funeral and the scene is probably set in the Luxborough valley in the vicinity of Langridge Mills a favourite painting ground during this period and only a couple of miles from his home at Beggearnhuish. This was not to be North's last involvement with Jefferies. In July of 1890 Arthur Kinglake issued yet another appeal, this time to support the erection of a memorial bust in Salisbury Cathedral. Margaret Thomas was the selected sculptress and North dutifully volunteered to be a member of the organising Committee. The other committee members were the RJF Trustees Besant, Longman and Buckley together with Kinglake, North, Osborne, C P Scott, George Smith, Andrew Lang, Mr Burdett-Coutts, Walter Pollack, Andrew Chatto, Ambrose Goddard, H Rider Haggard and F G Heath. The cost of the bust, £150 was slow in coming and in

the end Besant himself made a generous donation that allowed the project to be completed. The sculpture was undertaken using the London Stereoscopic Company photograph that North had obtained and was supervised by Jesse and Besant. The marble was completed in 1891 and was unveiled by Bishop Wordsworth on Wednesday 9th March at noon on a stormy spring day. As an aside, a copy of the bust was presented in 1925 to the City Council by Frederick Sutton a local confectioner and Mayor of Salisbury. It stands in the Committee Room of the Council Offices where it may be viewed on appointment. On 19th February, 1884 North was married to the 21-year- old Selina Weetch at Bicknoller Church in Somerset. Selina was the daughter of Abraham Weetch a local farmer. The couple moved into Beggearn Huish House in Nettlecombe rented (according to Berta Lawrence) from the Wyndham family. In this comfortable sandstone house with its stables and orchards,

they cared for North's widowed father and brought up six children, two other children having died in infancy. It was while he lived here that Herkomer came to study North's watercolour technique completing small watercolour portraits of North and Macbeth (who lived a few miles off at Bilbrook on the Road to Minehead). Selina herself died in 1898. It seems as though, at this time North may have made at least one further trip to Algeria. As a widower North lived first at Newlands House at Bilbrook, where Robert Macbeth had a house and then, from 1904 to 1914, at Withycombe. In 1885 William Graham MP, North's friend and patron died, in the same year north finally sold the house he had designed and built in Algiers. In the same year he first exhibited at Manchester, giving his address as 148 New Bond Street, London, which may well have been a studio. In 1888 North became one of the Consulting Committee at the New Gallery

and wrote to C W Deschamps severing his connection with the Grosvenor Gallery. North campaigned against the Game Laws writing letters to the local Somerset newspapers under the name John Lackland. The purchase by the trustees of the Chantrey Bequest in 1891 of North’s sad and symbolical painting 'The Winter Sun' (Tate, London), a work which Herbert Alexander claimed as influential on the rising generation of landscape painters, was said to have been due to the influence of Frederic Leighton. Hubert Herkomer, in his 1892 Slade lecture, claimed that North was the originator of the Idyllist style of landscape. This may have been uncomfortable for North as it sparked a debate over the relative influence of North and his late departed friend, Fred Walker. Herkomer, was an artistic chameleon, one moment the torchbearer for the young 'social realists' the next the portrait painter to the aristocracy. There is a certain

ostentatious self-importance about Herkomer that is inescapable from his memoirs and while North had a firm view of his own worth, he had a much more ascetic humble nature. In some ways it may seem that Herkomer used North as a stepping stone for his own ambition - drawing from him the secrets of his watercolour technique and with it a self proclaimed role as defender of the Walker style. Herkomer later destroyed North's correspondence, so we will not know for sure how the relationship between these two men played out. However, a final rift occurred when it emerged that North had opposed Herkomer’s candidacy for the Presidency of the Royal Water-Colour Society. From 1895, North devoted time and money to a business making drawing papers, and particularly one called ‘O.W. Paper’. Its failure left him virtually destitute and he depended in old age on a small pension from the Royal Academy. North died on 20 December 1924, at

Stamborough, a farmhouse high in the Brendon Hills that was his last home. He was buried in Nettlecombe cemetery. Selected Reading Hubert Herkomer, ‘J.W. North, A.R.A., R.W.S.: Painter and Poet’, Magazine of Art, 1893, pp.297-00, 342-8 Jefferies.G. Marks, The Life & Letters of Frederick Walker, London, 1896 Gilbert Dalziel 'The Publishers' Circular and Booksellers' Record of 10/1/1925 Herbert Alexander, ‘ John William North, A.R.A., R.W.S.’, Old Water- Colour Society’s Club Fifth Annual Volume, 1927-8 R.M. Billingham, ‘A Somerset Draw for Painters - Victorian Artists at Halsway Manor’, Country Life, 18 August 1977, pp.428-30 Berta Lawrence, ‘A Painter in West Somerset’, Exmoor Review, 1983, pp.55- 8 Scott Wilcox and Christopher Newall, Victorian Landscape Watercolors, exhibition catalogue, Yale Center for British Art, New Haven, 1992 Paul Goldman, Victorian Illustrated Books 1850-1870 - The Heyday of Wood-

engraving, London, 1994 Allen Staley et al, The Post Pre- Raphaelite Print, exhibition catalogue, Miriam & Ira D. Wallach Art Gallery, Columbia University, New York, 1995 Paul Goldman, Victorian Illustration - The Pre-Raphaelites, the Idyllic School and the High Victorians, Aldershot, 1996 Last updated: 13/05/2005 12:10:09

|